Japonisme

The press release puts it rather succinctly: “Japonisme celebrates cross-cultural dialogues in Australian contemporary art.” Japonism, or Japonisme, the original French term, was first used in the late 19th century to take account of the influence of the many Japanese forms that were reaching the west and gaining in popularity. Japanese ceramics, enamels and bronzes, and the wood block print were vital influences on French painting at the time and transformed early Modernism. They are, as this exhibition would attest, of influence still.

Each artist of Japonisme makes some connection with Japan in a formal or stylistic way, or by technique. Where the discipline of an art form such as ceramics may be grounded in Japanese culture, we are to find it here, mirrored in local culture, adapted and taken on in new ways. Or, as is the case with painted form and the graphic mark, we can trace influences to travel and the immersion of artists in Japanese culture. This is perhaps the aesthetic stance that the exhibition supports which, by reference, holds a mirror to forms such as origami and calligraphy. Indeed Japanese gardens count as well because nothing is to be considered in a literal sense. It is obliquely felt in the cut and fold of paper, or in fine spiralling lines and translucent glass.

To return to locality and the crossover potential of this exhibition we find that of the seven artists exhibiting, two, Miki Kubo and Mami Yamanaka, are Japanese born and are domiciled here in Australia. Liz Shreeve has her roots in the United Kingdom, David Pottinger is a Queenslander, Lucille Martin hails from Perth and Titania Henderson is Dutch and arrived in Australia in 1956. Guy Stuart, the long established painter, has visited Japan numerous times. They are an interesting bunch to bring together, diverse, yet all achieve a high level of finish, with ideas that speak through their material concerns.

The art of glass occupies a distinctive place in the craft spectrum. There is a dedicated group who appreciate and assiduously collect glass but there is otherwise little critical acceptance of glass in mainstream art and criticism. This is surprising when you think of the tradition of glassware which stretches back through time to early function and to the decorative pieces of the Middle East, for example.

The glass artist of this exhibition, Miki Kubo, was born in Kyoto in 1971 and has lived in Australia for more than a decade. Her works are beautifully realised pieces that speak of fine craft and solid technique. She is a relatively young artist with a following both here and in Japan and it is obvious from her iconography (the Goldfish, the Frog and the Gecko) that Australia is a great influence upon her.

David Pottinger is also an artist of some note whose work is in all major Australian collections and in the Victoria & Albert Museum, London. He has also been the subject of essays by Emmanuel Cooper and leff Snyder so there is discussion around what he does. To create vessels, Pottinger uses the traditional Japanese technique of neriage which involves fusing different col-oured clays that have been cut and layered. The results are refined and the aesthetic bespeaks calmness and purity. There are three such vessels in this exhibition each one immaculately weighted and finished. They do not claim attention as much as they bring you back to thoughts you had put to one side. It is a ceramic art of the first order.

Titania Henderson is also an accomplished ceramic artist with marvellous facility. She uses sheets of porcelain that She fashions into organic forms. The work seems perfectly formed, as if untouched by hand. There are curlicues and circles played against cuts and folds. If is something you might imagine in sheet steel, or enlarged to fill a quiet numinous space. The titles suggest this (Circle of Life, Tip of Light 1) and the aesthetic further confirms her intentions: whiteness, clarity and poise.

That perhaps Henderson’s forms relate strongly to paper (paper thin, folded and cut) leads to the work of Liz Shreeve. Paper is her medium but painting remains her inspiration. I am thinking here of post war American abstraction and the grid, Agnes Martin and minimal sculpture. The four works of the exhibition are subtly modulated square relief pictures. There is not much between them as they are all the same size and carry similar cuts and folds. It is the colour of each that alters our perception, from green to blue and orange to violet.

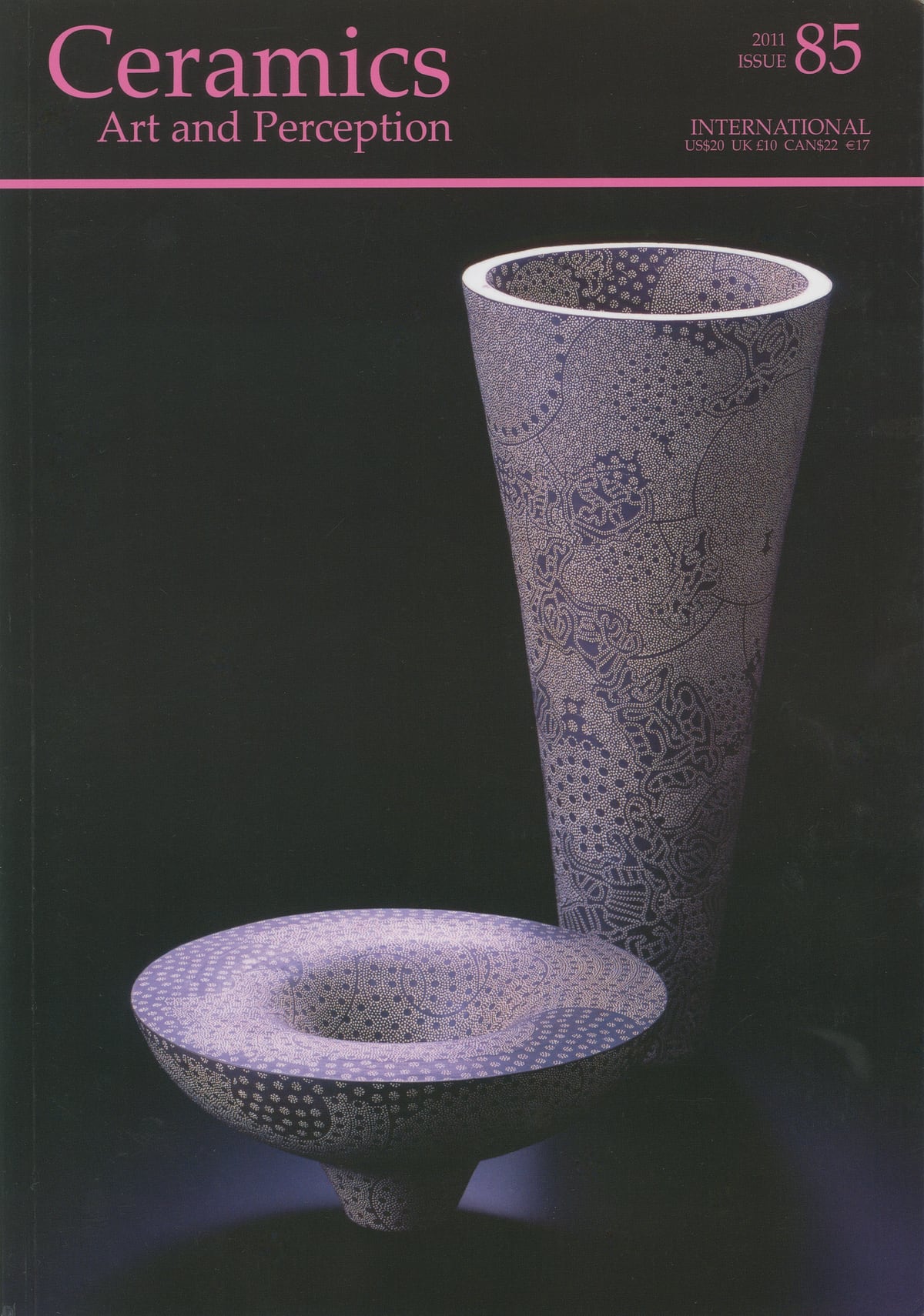

Mami Yamanaka is consumed by pattern and repetition. Her works appear to be the equivalent of computer animated design; such is her skil in rendering intricate forms. I wonder whether the artist is using design pro-sans or is her intention to make a critique of the same? nole that Yamanaka once held an exhibition called Constellations and this would seem an apt title as her drawn shapes are placed in clusters and then reformed again. These formations are a challenge to the retina; the eye never quite rests and is drawn forward and back ceaselessly.

Lucille Martin is an assembler of found things for the most part. This method of bricolage has been in Modernism since Picasso first experimented with collage and Kurt Schwitters carried assemblage into the total environment. Martin is perhaps more of a formalist and likes to place her objects carefully; their edges touch and various textures overlap. These are not raw and confronting works. Her assemblages acknowledge but do not forcefully make the point about recycled culture and high and low art. They are, however, bound by a desire to create beauty and order amidst a turning world.

Stuart seems the least likely of this complement. On balance this is a good thing because Stuart has a strong understanding of painting and the traditions of Japanese art. Guy Stuart is by definition a modernist and, like Fred Williams who was no stranger to Oriental modes, he equates notation with form and matches colour to sensation. These attributes along with lyricism and economy are what he shares with the other artists of this intriguing exhibition.

Brett Ballard